I, Reinhard Jung, was about three years old when I asked my grandmother where God dwells. She answered:

"God is everywhere, He is spirit, He is omnipresence."

I still recall to this day how that answer made me happy and I was completely satisfied as if some inner knowledge had been revived. Perhaps a child is closer to inner understanding than we imagine: "Except ye be converted, and become as little children, ye shall not enter into the kingdom of heaven..."

Today I remain grateful for the Christian education that I received from my parents, although my view of its scope has considerably widened and deepened over the years. To begin with a child needs images and immediately senses much more in them than it later learns through words and ideas.

There followed some years of belonging to the YMCA under an inspiring leader. It was an appropriate training at that age, with an emotional kind of religiosity associated with fellowship, campfires and boy-scout romance.

Then came what was probably the necessary rejection of childish ways in a difficult adolescence which eventually led to a deep crisis that gave birth to a burning question about the meaning of life. About that time I learned the technique of Transcendental Meditation (TM), which almost immediately brought me to a deep inner silence. This meditation, with an intensity previously unknown, opened my heart and senses to receiving the beauty of Nature, which until then I had been ignoring completely. It was the contrast between inner beauty and security on the one hand and a totally confused exterior life on the other that caused the crisis to become acute. One of the triggers for this great difficulty may have been the experience of drugs, which were praised in those days as being new and mind-expanding and which had captivated a large section of the younger generation.

Out of a deep existential fear arose, with great clarity and urgency, the following question: If the hippie culture, rock music and hedonistic life-style represent a dead-end, then what is the true meaning of life? The strong and beneficial impressions of meditation subliminally pushed me in the right direction. These wholesome impressions were so different and so much more real than anything I had known until then at the age of eighteen. Another question arose: Is there a God? I immediately realized that God, if he existed, must be universal, i.e. transcending different cultures and religions.

At home I found a book by Helmut von Glasenapp, a famous scholar of religious studies, which was about the five major world religions. I read this work with great interest, but above all with the intention of finding the common ground those religions shared. It was meditation that chiefly attracted my attention and very slowly through many doubts, the insight emerged that actually there always has existed, and still does exist, such common ground. Over many years I followed this direction. At the beginning my insight was little more than a hint, but over time I found this intuition more and more convincing. There are, and always have been, living witnesses who have experienced for themselves an inner transformation. And all these people were speaking the same language. Even in the 13th century, when hardly any channels of communication existed between Europe and Japan, one finds utterances of Meister Eckhart that are sometimes almost identical to those made by Dogen, a famous Zen master who lived about the same time. This fact seemed to strongly support the scientific nature of inner experience.

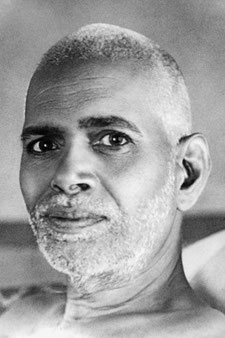

For me, the most radiant example of someone with universal vision has been Sri Ramana Maharshi, whose photograph touched me deeply, and who also convinced me, first through his charisma and peace and later by means of his teachings.

My own meditation practice deepened as I continued my practical research, and I attended courses during which it was possible to be silent for several hours a day. Through this, I was gradually gaining a better understanding.

In the early 1970s, during a visit to Seelisberg in Switzerland, I decided to attend a training course as a TM teacher. The time spent in community with other young people from all over the world, all of whom were living contentedly together, felt like a tremendous liberation from the tedium of everyday school life. The training course lasted three months, but with the help of my parents I was able to extend it for a further three months.

The experience of a time filled with such grace cannot really be communicated. The deep faith I developed in the healing power of silence, which gave such comfort and inner security, has left a profound impression on me, which has never been erased.

Our education should develop an awareness of the silence within us, and not only just train our memory. Young people would then develop a natural sense of the beauty and sacredness of life. Christ's expression,

"Seek ye first the kingdom of God, and His righteousness; and all these things shall be added unto you" took on a fresh and vivid meaning for me.

Of course in the beginning the clarity and lightness of being did not remain with me all the time. It became evident that this refinement of mind needed to be stabilized in everyday life. The next steps were to be my training as an alternative practitioner and the changeover from the Transcendental Meditation movement to a spiritual teacher who could guide me personally on the inner path.

In 1980 I established a practice as a naturopath in the town of Oberstaufen, and by now I had a wife and three children. I was grateful for a free way of working, in which I was able to refine and further develop a range of therapies, from physically-based cures to guidance in meditation. The patient has always been a teacher for me also, and many people have approached me over the years as someone to be trusted.

I soon started to offer courses and I began with Autogenic Training, as I was not sure what was going to prove most acceptable to the general public. But because I was not convinced by this rather mechanistic and auto-suggestive technique, I soon developed my own variation on it. This I called 'Eutonie' or 'Eutonic exercise', a term which I borrowed from Gerda Alexander, because it described best what I was trying to express; this was the creation of a deep relaxation and well-being, by means of systematically listening to the body.

These courses proved very popular and were attended by many people. I once estimated that over the years about 15,000 people must have taken those courses. There soon emerged a core of young people who felt particularly involved. We undertook weekend seminars together and we started to meet more regularly. The teaching developed logically from our conversations. It was not so much that I personally was 'the teacher' - although for all practical purposes I was and still remain a teacher - but more that 'Satsang' evolved; in the mutual exchange of ideas and searching for the truth, our own language and form of expression emerged through everyone who was involved.

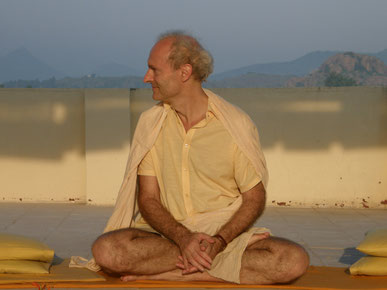

This circle of friends came into being some thirty years ago and continues to provide me with a living and a creative way of life as well. Today these friends are all connected by their wish to live in a spiritual manner. Besides the weekly satsang, everybody attends a monthly contemplation and an intensive weekend seminar. Three longer periods for reflection are also offered. One of these retreats is in South India at Arunachala; another is held in Sardinia during the Whitsun holiday and a third in August takes place in a cabin in the Austrian mountains. In their daily life, everybody follows these inner practices and this way of life could be described as an open monastery. A multitude of exercises and a lot of learning material has developed over time. It is amazing to see how creative these gatherings are. Although the teaching is familiar, everyone experiences it as fresh and inspiring. The Buddha called three elements of his teaching holy: The Buddha, the Dharma and the Sangha. In our case this means acknowledging the authority of the teacher.

As a teacher one is often required to share the intensity of the inner process of transformation with one's students. In my case this naturally led me to find a suitable and supportive lifestyle. For years I have been spending weekends in Nature to recuperate on all levels and to live in accordance with the principles which fit this wonderful, but very demanding way of life. With my second teacher, but also with other teachers (for example Ajahn Chah), I could see what happens when this opportunity to rest and recuperate is lost. Chronic illness and premature death were the consequences. Besides, long before that happened, one's example would no longer be convincing. The entire inner path is based on a composure that needs to be nurtured. When this serenity is missing, the quality of guidance decreases and it has often happened as a result that the dark side of such teachers becomes evident - and the whole community has to suffer for it.

Over the last three years I have been living in India for four months at a stretch. This gives time for 'Sadhana', which is what they call spiritual practice in India, to mature and grow. For this reason, Ananda Mayi Ma, one of the most important saints of India in the last century, called Sadhana 'Sva-dana' - self-wealth.

This website is intended to awaken and facilitate awareness of the fact that the quality of our existence does depend essentially on our inner condition. Its aim is also to kindle interest in directing one's own life to the great Truth, which alone can give our lives permanent meaning and depth.